In the study of identity, the debate between essentialism and non-essentialism has profound implications for how we understand ourselves and others. Holliday Kullman and Hyde (2017) explore this distinction, shedding light on how these perspectives shape our views of gender, race, culture, and more. Let’s break it down with some real-world examples to see how these ideas play out in everyday life.

Essentialism: The Fixed Lens

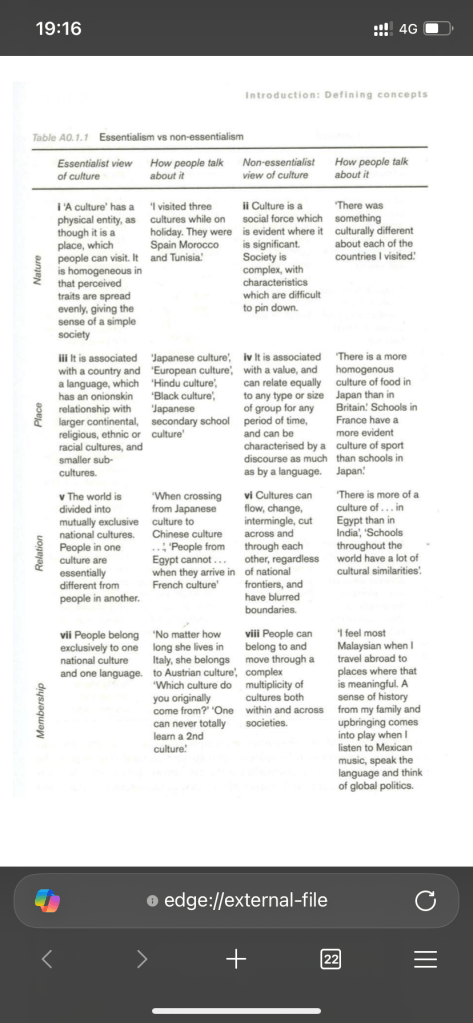

Essentialism is the belief that certain categories—like gender, race, or nationality—have an inherent, unchanging essence. This perspective assumes that these traits are biologically or culturally predetermined and define who we are at our core.

For example:

- Gender Essentialism: The idea that men are inherently aggressive and women are naturally nurturing is rooted in essentialism. This perspective assumes that these traits are fixed and universal, ignoring the diversity of experiences within genders.

- Cultural Essentialism: Statements like “All Italians are passionate” or “All Asians are good at math” rely on stereotypes that assume a shared, unchanging essence within a group. These generalizations overlook individual differences and the fluidity of cultural identities.

While essentialism can provide a sense of stability or clarity, it often leads to stereotyping, exclusion, and rigid boundaries that don’t reflect the complexity of human identity.

Non-Essentialism: The Fluid Lens

Non-essentialism, on the other hand, challenges the idea of fixed categories. It argues that identities are socially constructed, context-dependent, and constantly evolving. This perspective emphasizes the diversity within groups and the role of social, historical, and cultural forces in shaping who we are.

For example:

- Gender as a Social Construct: Non-essentialism views gender as a spectrum rather than a binary. It acknowledges that traits like aggression or nurturing are not tied to biology but are influenced by societal expectations and individual experiences. This perspective allows for the recognition of non-binary and transgender identities, which essentialism often overlooks.

- Race and Ethnicity: Non-essentialism recognizes that racial and ethnic identities are not based on an unchanging essence but are shaped by historical context and social power dynamics. For instance, the meaning of being “Black” or “Latino” varies across time and place, reflecting the fluidity of these categories.

Non-essentialism encourages us to see identity as a dynamic process rather than a fixed trait. It opens the door to greater inclusivity and understanding, challenging stereotypes and rigid categorizations.

Contrasting the Two: A Real-World Example

Imagine a classroom setting where students are learning about historical figures:

- Essentialist Approach: A teacher might present historical figures as embodying fixed traits of their gender or race. For example, describing Rosa Parks solely as a “quiet, obedient woman” who sparked the Civil Rights Movement reinforces essentialist ideas about gender and race, ignoring her activism and the broader social context of her actions.

- Non-Essentialist Approach: The same teacher could highlight how Rosa Parks’ identity and actions were shaped by her social and historical context. This approach would emphasize her agency, the collective efforts of the Civil Rights Movement, and the fluidity of identity in shaping history.

Why Does This Matter?

The debate between essentialism and non-essentialism isn’t just academic—it has real-world consequences. Essentialism can perpetuate stereotypes, limit opportunities, and reinforce inequalities. Non-essentialism, by contrast, promotes a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of identity, allowing for greater empathy and social progress.

As Holliday Kullman and Hyde (2017) suggest, moving away from essentialist thinking can help us embrace the complexity and diversity of human experience. By recognizing that identities are fluid and socially constructed, we can challenge stereotypes, celebrate individuality, and build a more inclusive world.

So, the next time you catch yourself making assumptions about someone based on their gender, race, or culture, pause and ask: Am I seeing them through an essentialist or non-essentialist lens? The answer might just change your perspective.

Leave a comment